Let’s continue with our series on a Defender’s Toolkit. Today, we’re going to discuss Regular Expressions!

Regular expressions (or regex) allow you to search through texts for a sequence or pattern of phrases or strings. These sequences are nothing but ASCII or Unicode characters in a particular order. The use-cases of Regex are unlimited; from parsing to extracting key information, translating data from one type to another or web scraping, it’s used for all these tasks and more.

You might also make use of these regular expressions in scripting or programming languages, or perhaps on the command line. Often, you’ll be required to sort through tons of data on the terminal or pick a single process with a unique name from a list of processes - that’s where ‘grep’ with a regex search pattern can come to your help.

Now that you know where we might utilize this tool, let’s discuss the basics of regular expressions, its syntax, and some key examples where regex will make our lives easier.

Before we move on, here’s a sample regular expression:

[A-Za-z\d/\-:.,_$%\x27"()<>= !\[\]{}@]{4,}

What sorcery is this? Regex!

Is that how you reacted to this regular expression? It’s cryptic for sure!

Rest assured, by the end of this blog, you’ll have a much better idea as to what all those characters or weird phrases mean. Let’s get started with the Regex jargon already:

Meta-characters

Like every other tool, regular expressions also have a few characters that have special meaning in it’s usage. These characters are nothing special but those which you already use in your ASCII-based strings. However, they’re called ‘meta-characters’ in the regex world. Let’s take a look at some of those and their particular meaning:

Anchors

Anchors can help you pick a string based on its starting and ending characters. For anchors, you’ll be using ‘^’ to identify the start of a string and ‘$’ to identify the end of a string.

Let’s check them out in action. Wait, where do you test regular expressions? Luckily, there are tons of regular-expression engines, IDE’s, or text-based software which can help you do that. I’m currently using Regex101, a web-based regex engine, which you can use as well. regex-101

Now that it’s clear how, let’s see what I mean by using anchors:

| ^Quick | Match a string starting with ‘Quick’ |

| Hero$ | Match a string ending with ‘Hero’ |

| ^Dog$ | Match the exact string ‘Dog’ |

| lazy | Match ANY string that has ‘lazy’ in it |

| ^Quick brown fox$ | Match a phrase that has the string ‘Quick brown fox’ in it |

If we run these through the text:

Quick brown fox jumped right over a lazy dog...

He's a Hero

Dog

He's so lazy

Guess what expressions will match? Expression 1, 2, 3, and 4, will match. But, why doesn’t the fifth one match? We do have the string “Quick brown fox” in the first sentence. It’s because anchors only match a particular section of a string and they shouldn’t be continued with a whitespace, special character, or other characters. If you run the same rule on “Quick brown fox” - you’ll get a match!

Non-printable Characters

You can’t see new-lines or line-breaks, can you? But you might want to capture them in order to exclue or include them later on. You can do that by making use of non-printable characters which are used in several programming languages as well. Here’s a small list of the most commonly used non-printable characters:

| \n | Line-feed |

| \r | Carriage return |

| \t | Tab Spacing |

| \r\n | Windows-based line feeds |

Character Classes

Character classes or character sets allow you to select a single character from a list or set of characters. You can make your own character set by placing several characters in between square brackets. For example, you can use [aeiou] to capture all vowels in your text.

Here are some more examples:

| [a-z] | Match all lower-cased characters from ‘a’ to ‘z’ |

| [A-Z] | Match all upper-cased charracters from ‘A’ to ‘Z’ |

| [0-9] | Match numbers from 0-9 |

Let’s say you want to write your text that’s suitable for both UK and US english. Is it ‘gray’ or ‘grey’?

gr[ae]y

will match both ‘gray’ and ‘grey’. One other example would allow you to find hexa-decimal strings amongst others:

0x[A-Fa-f0-9]

will match the strings: 0x3A, 0xAA, 0xFA

Short-hand Character Classes

See some repetition in there? You’ll most likely be using numeric ranges or character ranges again and again. That’s precisely why we have shorthand character classes which can abstract this into a simple line. How? Let’s see some examples

| \d | Stands for digits and will match anything from 0-9 |

| \w | Stands for word characters and will match anything in the ranges, a-z and A-Z (some engines include 0-9, _, and some other symbols) |

| \s | Whitespace character which will match all spaces in the text |

If we re-write our expression for the hexa-decimal strings, it’ll become:

[\dA-Fa-f]

Why not use ‘\w’? Because it includes more characters and hexa-decimal strings max out at ‘F’ or ‘f’

Negated Short-hand Character Classes

What if you don’t want a digit? You can negate the effect of the character class by adding the ‘^’ symbol infront of it. Here’s how:

[^\d]

This works for all characters and sets. But, again, this can be abstracted as well. So, regex provides you yet another easy way of negating a classes’ effect - simply upercase the letter you use to signify its meaning.

Here’s how:

[\D]

Will match anything that’s not a digit. Similarly:

[\W\S]

Will match anything that’s not a word and isn’t a whitespace. But wait, let’s run it through the engine. What happens? It’ll match everything! Why? Because the character class can match any one of these and the ‘\S’ set indicates it should match a non-whitespace; which is practically EVERYTHING!

Quantifiers

If you check the results, it’s matching the string but it’s character-wise. If you return the results, you’ll get characters - what’s the point in that? Often, you’ll want to repeat your character set such that it creates one whole word, or one complete digit with all numbers, or something like that. So, we use ‘quantifiers’ to make sure our sets repeat.

We can make use of these three quantifier meta-characters:

| * | Repeat character class one times or more |

| + | Repeat character class once or more |

| ? | Render a character class optional (match zero or one instances of something) |

Here are a few examples of these operators:

\w+

\d*

These will match words and digits and repeat the classes until a whitespace or a non-conforming character is observed which will break the character set (character during the digit check). We’ll see how the ‘?’ operator works, next.

Greedy Operators

We talked about the ‘?’ operator which can help you with optional matching. However, there’s another feature to it: It’s greedy. See, it presents the regex engine an option to match the expression or leave it be. But, it will always match the entire string and only then, decide to fail it (it won’t leave the optional set just because it can be left out).

Run this regular expression:

April 15(th)?

On the text: April 15th, 2020. The match will always be “April 15th”. This is called its greedy property. However, there’s a lazy operator as well, and its features are the direct opposite of the greedy operator. Though we’ll discuss this again, you can make the “?” symbol lazy be repeating it twice, such as:

April 15(th)??

It’s lazy now and won’t go through the trouble to exhaust itself trying to find a match - et voila! By the way, the ‘?’ doesn’t just make the ‘?’ lazy - it can be used with groupings, +, or the * operators as well (we’ll discuss groupings).

Escaping Characters

What if you want to match a meta character? You can escape it using the back-slash or ‘' operator. Simply write ‘\?’ to match the literal ‘?’ in your text!

Similarly, if you want to match all characters, despite their occurence, you can use the ‘.’ symbol. This isn’t the greatest method to pick characters but works in cases where being tidy isn’t a requirement. Give it a run and see if it matches all characters.

One tip is - never over-use the dot! You should make use of negated character sets or keep the usage of the dot minimal to avoid issues with extracting intended data.

Boundaries

If you’d like to capture a word that’s not bounded by an character or separated by a whitespace character, you can use word boundaries. It’ll match the word as many times as it appears in the text and isn’t followed by any alpha-numeric character(s).

\bHi\b

Will return ‘Hi’ on the text ‘Hi there’ and no results on “I’m Hilarry” (because it’s followed by an ‘l’). If you wish to negate this effect, you can use the ‘\B’ identifier which will negate the effect

Alterations

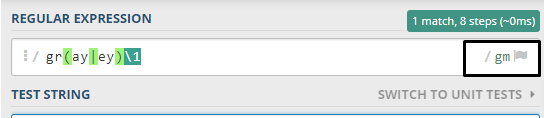

At times, you’ll want to select either one of a few regular expressions from a list. Unfortunately, the character classes only help with the individual characters. You can utilize the paranthesis ‘()’ symbol to group a few expressions together. Using the ‘|’ symbol with these can help you alternate between the choices. Let’s see how it works:

gr(ay|ey)

This will match both ‘gray’ and ‘grey’ on separate lines. Because now the expression can alternate between the two options you’ve presented. This is called ‘grouping’ of expressions together and is a powerful feature.

You can use the ‘|’ to alternate between two expressions without using the grouping feature and it’ll still work. Using ‘ay|ey’ will work on ‘ay’ and ‘ey’ as well.

Back-references

Let’s say you’ve used the alterations in your expression. Now that it’s done, when you check the matched portions, you’ll have captured groups or better called ‘capturing groups’. This will be the text or the string which was matched using your regular expression from the provided or sample text. Once it’s in the captured group, you can utilize the match in other searches, and that is done via back-references.

| Back-references are used by the back-slash sign and a number, denoting the number of the capturing group. Let’s say, gray matches the regex gr(ay | ey), then since it’s the first match here, the term ‘\1’ will hold the match ‘ay’. You can use the regex like: |

gr(ay|ey)\1

To match ‘grayay’, which doesn’t serve a purpose but does the deed. Similarly, the numbers will increase, just as your capturing groups increase. Here’s an example with two capturing groups:

(hi|Hi)\s(there|Hasan)\2

Now, I’ll match the text: ‘Hi therethere’ and this works perfectly! One final tip - back-references are actually faster and can help the regex engine find a match much faster.

Quantifiers (Revisited)

There’s another way to repeat the same character class and that’s using the curly braces, {} and specifying the limits such as: {min, max}. They’re similar to the quantifiers we’ve studied before but they had no end limit. It would either be 0, 1, or unlimited.

We can control the upper bound by using this techniques. Here’s how:

[aeiou]{1,3}

[hasan]{5}

[hasan]{2,}

[hasan]{0,}

[hasan]{1,}

The first expression will match 1 or 3 of these characters in the set, the second matches 5 times to be exact, and the last expression requires 2 or more (unlimited) matches on the characters in the set.

The {0, } is actually the ‘*’ operator, whereas the {1, } expression is actually the ‘+’ operator. They’re abstracted but can have these meanings as well.

Regex Matching Modes

The regex matching modes are defined below and are supported by many regex engines:

- /i makes the regex match case insensitive.

- /s enables “single-line mode”. In this mode, the dot matches newlines.

- /m enables “multi-line mode”. In this mode, the caret and dollar match before and after newlines in the subject string.

- /x enables “free-spacing mode”. In this mode, whitespace between regex tokens is ignored, and an unescaped # starts a comment.

- /g enables global matching

You might find these on the right side of the editor on Regex101.com, if you’ve been using that.

Where to Next?

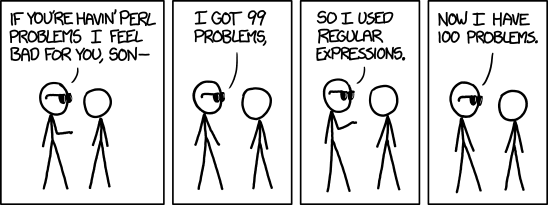

I’ll be ending the blog here, but there’s much more to Regular Expressions and that’s what my Regex 102 lesson will be all about. It should be up really soon, but till then, I want you to practice on the craft! Here’s a famous picture on Regex:

But, let’s not be this guy.

You can find cheatsheets, lots of interesting lessons, and practice forums on the web. For one, you should complete the Regular Expressions series on regexone.com in order to fully practice the basics of it!

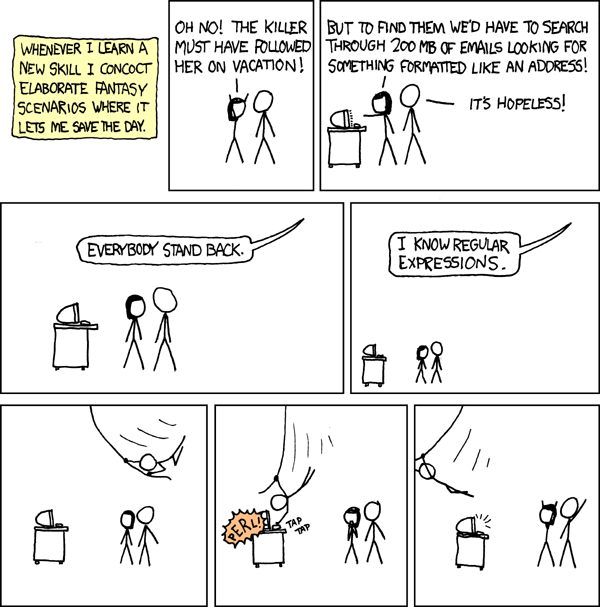

Then, you can make your own regex on Regex101.com and become a master of it. Let’s be the hero we’ve always wanted to be in the field of forensics. Here’s one:

Practice, practice, and practice. You’ll be perfect at Regular Expressions and that’s when searching and parsing through tons of data won’t feel like a deadly assignment to you!

Till then, goodluck! Stay Safe!